John Airfield talks old cars and new friends, shares music video

Ahead of his new music video for “Don’t Wanna Come Back,” Michael Steiner sat down with Ayla Stabile and Sarah Katherine to discuss his music as John Airfield, how countless red eye flights between New York and California became the inspiration for his first musical project in over a year, and how the new music video, directed by Maria Rusche, helped unpack nostalgia from early queer experiences.

Interview by Sarah Katherine and Ayla Stabile

Photography by Chris Bernabeo

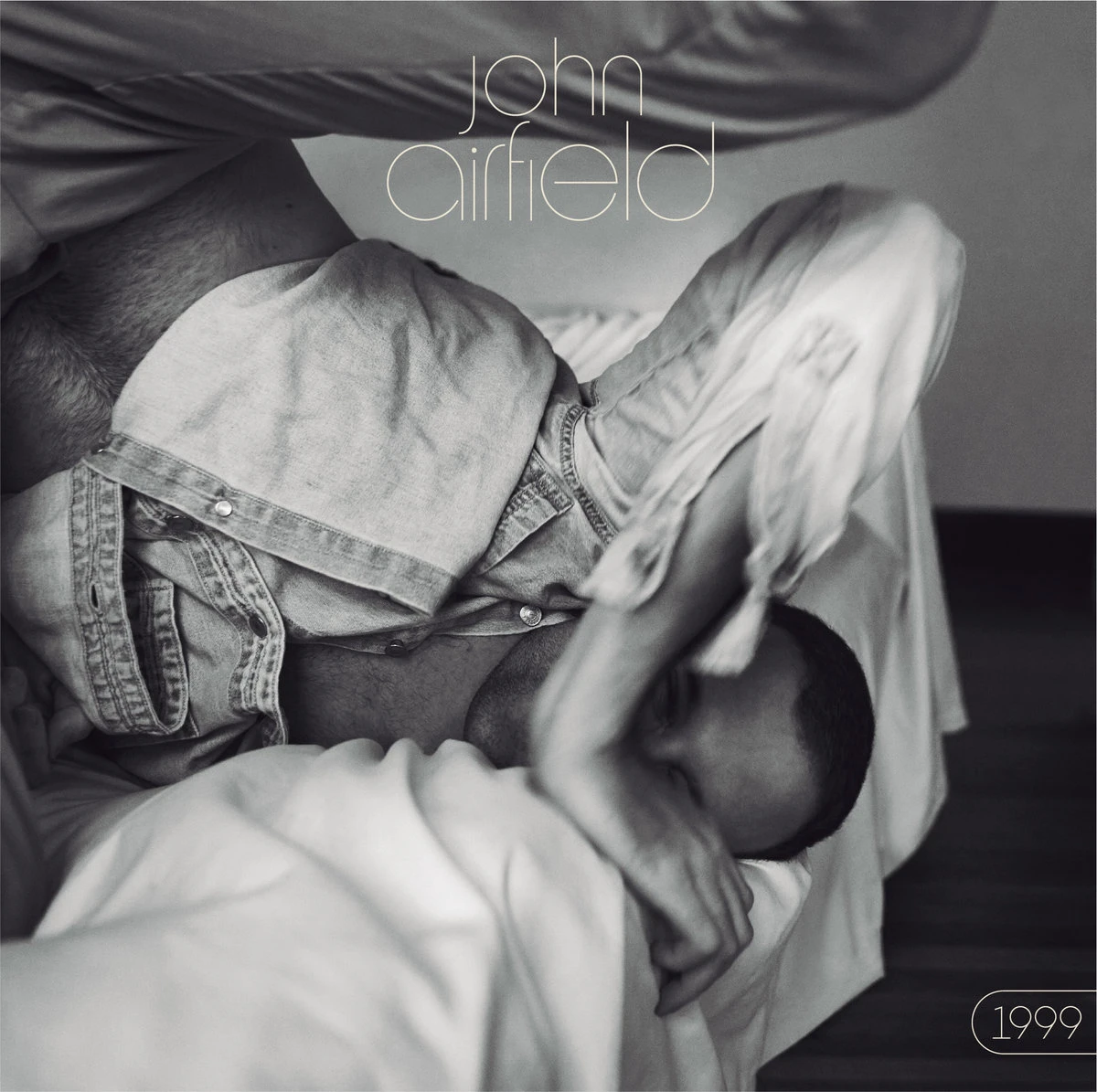

In coordination with Funnybone Records

Music Video for John Airfield's "Don't Wanna Come Back"

Ayla: So, why 1999? I know you mention it in the lyrics..

Michael: There is a lot of nostalgia, and I think that when people hear 1999 they can see there’s that element to it, but it’s actually much more specific and silly. The visual for the first song “Don’t Wanna Come Back” is kinda where it started. It’s all about driving, when you would just go for drives with people in your hometown, when you’re home for the holidays or from college or whatever it is, and the activity is just driving around. And there’s a car, it’s a 1999 Saab hatchback and for some reason that is what stuck out to me. I’d also trade that in with a Volvo station wagon. I’m not like a car person but it’s something about that era of car, and just going to someone’s house to say let’s just drive for like an hour and a half and waste gas and go to Wendy’s, and drive down fun streets...that’s kind of where the visual started. In 1999 I was like 8, so that’s not really the time period, when you talk about high school and forming identity and stuff like that, it’s really just about this hyper-visual of your friend’s dad’s car or something.

Ayla: I really dig that! I’m not much of a car person either but the Saab definitely has a specific vibe…

Michael: I was just home in West Hartford and I drove by my friend’s house and saw the car and had a full circle moment, even though the memories that the song is about don’t really pertain to that car. Nothing special happened in that car (laughs) it just kind of embodied everything from the high school parking lot.

Sarah: That’s so cool, I love hearing the stories behind it. Who else was involved with the project and how did the connections all come together?

Michael: So, before the John Airfield project, and since senior year of college to like, a year ago, I was playing music with the band called Noble Kids. Everything I did, first shows, first recording, first everything was with them, it was really fantastic and fun, with the same 3 or 4 people. Then people started to move, and Noble Kids ended and for the first time ever it was just...me. I didn’t stop playing music, but I had no idea what to do next. I love to play a lot of different instruments but I don't consider myself particularly trained at a lot of them. I wasn’t even sure if I felt comfortable recording something. I’ve always loved to sing and I feel good about that but I was like, are you really gonna play guitar on a record? Are you gonna do this?

So it became the obvious thing to say well you don’t have to do it alone, you have friends and people you look up to. So half of it was my close community and just reaching out saying “hello, i want to make music again.” I think the first person was my friend Griffin [Emerson] who’s a producer, was a great technical person and also a spiritual guide. He was in LA, and this is a time when you could leave your house and travel...I was flying back and forth from the east and west coast for work so I decided to sneak over to his neck of the woods. He was a positive, reassuring force saying “If you want to make music, let’s make music..stop being afraid of this let’s just start”. So one weekend we made, just him and I, a fun poppy song just to see what was possible, one that probably won’t see the light of day, but he was showing me that we could do whatever we wanted together. At that point we started reaching out to feature other people on what we made, like Greg Dyson, a friend from high school who was probably the first person I knew who had a high school band. I’ve always respected how he writes music so when I was writing the first song, before we even spoke, I was trying to write a verse like he would sing it. And then I just reached out to him and he was excited. That’s how all of these things were built. There are some ambient drones on the second track from Ben Seretan, he’s such a wizard of weird noises and I wanted to fill out the song more. Because there is no band, it’s a lot of just thinking of people I want to connect with. I’m already thinking about a second EP, and now that I’m with Funnybone; there’s so many great artists and I just have to figure out which introduction to make. I want it to be this swirling thing, finding people that I look up to and respect and hope that maybe they can contribute even, say, 10 seconds to a song. That was long! But that’s how it’s been building.

Ayla: You mentioned someone from high school. So it’s pretty much the amalgamation of connections that you end up having through time and following music?

Micheal: Yeah, exactly, it’s one of the first people I ever saw play music and then one of the last shows I ever saw. Those are some of the people involved on this, so it’s super special. Even some of it is just friends of friends, and I think it’ll keep being that way. It always manages to be personal. It’s a great way to start expanding a community that feels smaller, especially right now because you don’t get to watch people play shows. That was the weirdest part, I mean everyone’s going through this: releasing a project and not having a show to go along with it, even if it was just in somebody’s backyard. It’s very different to just give it to social media.

“So that’s a very big abstract amorphous thing, but trying to encapsulate it and talking about what it felt to take those flights. Again, the visual of every time you land you see Coney Island and then you land at JFK, trying to put these hyper-specific things into the song.”

Sarah: Are you doing any live streams?

Michael: I’m working on it...I’ve seen some great ones but it’s a bit out of my comfort zone. In lieu of that I did record two live versions of the songs in a field with the help of a friend! I should also say, in terms of connecting with people, this was an exciting opportunity to go bigger with the visuals. You can’t ask everybody to help you make something express queerness. I don’t want to say if you’re not queer you can’t help express queerness, I don’t think that’s true, but the visual part of this record was a way for me to bring people into a larger space of things I’m trying to say. Making a video, there’s more senses involved, and I’m lucky enough to live with a really wonderful friend and photographer/videographer who’s also queer and I can ask about this stuff. I’m not saying I want to be draped in a rainbow flag, but I want people to feel the self-consciousness of how we think of our identity.

Anyway, he [Chris Bernabeo] and Sydnee Mejia who did all the design of the record, are people with whom I could have that conversation. How can we accentuate some of the things about identity in the visual, and maybe it’s super abstract but it felt really important that it wasn’t just music alone, that there’s ways to expand the world. Does that make sense?

Ayla: Totally. I mean I think, I don’t know if I want to say straightness, but stuff gets projected onto music so quickly that can undermine the queerness that it’s actually expressing.

Michael: Right!

Ayla: Which I guess you see happen in pop music a lot with like, queer idols who are then accepted by these people that would bully them.

M: Yes (laughs).

A: So I definitely appreciate the sentiment…

M: That’s really interesting because I also feel like, without trying to generalize a community, a lot of musicians who are not queer get lionized as queer icons in music. This isn’t my hill to die on, but because you bring it up, it’s interesting that part of a community is like lifting up voices of people who bullied you in high school, vs the many queer voices in the music community who could use support. The genre of “indie” is impossible because it’s something that gets an inherent masculinity or straightness projected onto it.

The Funnybone roster is really cool cause for me, a lot of the people on the roster helped me deconstruct that and made me feel like there was some queer indie genre out there that I want to belong to.

Sarah: Is that one of the reasons behind all the funds for this 7” vinyl going to Morris Home?

Michael: Yeah, I consider myself a working musician, I also am a working designer, I have a full time job doing industrial design and making things. Any other amount of time I have is music. In the past couple years I was extremely lucky that the job I had put me in a place where I could like, not have to be concerned about my resources to make music. It’s this really ridiculous thing where it's like, to allow myself to literally be able to afford to make music, I have to spend less and less time doing it. I'm so privileged that I enjoy the thing I do in the day time, and I love art, so I’m happy. But...it put me in a place where, when I started this project, knowing Noble Kids was done, that part of my musical life was over, and I want to make music. That’s what I want to do.

It wasn’t like, if I want to make music it needs to pay my rent. That’s not what I needed music for, so when I was thinking about what I wanted to do next, I didn’t even know if I could make a full album, I can play like one song at this point...So I said we’ll lets do an EP and let's have it be for someone else. I feel like that's what it should be. And I understand that not everyone’s in that place, and I’m not saying everyone should make music for a cause but, I found myself in this lucky position where it just made sense. There’s a billion causes out there but I asked some friends for ideas...I knew I wanted to support a cause for the queer community, but even within that it’s so hard to know what’s best. Morris Home came up with some friends who live in Philly, and what really struck me is that it supports something I absolutely take for granted. I never thought that if I needed resources for addiction and recovery that I would have trouble getting them and that was a “holy shit” moment. That was like, if I’m a queer person and that’s how I feel, then I cannot imagine how necessary Morris Home is, because of how overlooked that aspect of life as a queer person is. Back to letting someone else into the project, and being part of a community...I knew nothing about Morris Home or services for the trans and gender non-conforming related to substance use and recovery. It’s only part of this project because people were willing to help me figure it out. I, and Dylan [Healy] said it too, we want this to be a series and continue to find organizations like this...highlighting what might be overlooked.

Ayla: Totally! It was new to me, and gave my own little “holy shit” moment of like. One can imagine pretty easily that finding services for treating addiction and accessing recovery programs etc is going to be disproportionately difficult for trans and gender-non-conforming people.

Michael: As a quick sidebar...this same idea. Have you heard of Black Trans Travel Fund? It’s a direct mutual aid thing that aims to ensure, at least in New York, that Black trans people have safe access to Ubers. I so strongly believe in transportation and the ability to move around your world. It’s the door to everything, jobs etc.

So Black Trans Travel Fund was the perfect thing that took what ended up becoming really toxic about the world that my job went into, and turned it completely on its head. People don’t think enough about transportation for the queer community as such an essential, top need. Things like this, as well as Morris Home, are things that everybody needs but maybe people don’t associate them specifically with the queer community, as opposed to the community at large. I want more people to have the “aha” moment I had and start thinking about these issues.

“I’m sitting in my underwear with a guitar and just trying over and over again to make it happen.”

Sarah: Yeah, this specific EP actually talks a lot about traveling. I would love to know what your creative process looks like and how that incorporated travel and lack thereof because of the pandemic.

Michael: I think I always tend to write about big things and then get processed and output in very specific examples like the second song “Landing”’ came from all of the red eyes from San Francisco to New York and being shoved in the corner of these seats. And even then, I loved my work but it was crazy...it was super stressful. These red eye flights almost feel like they do not exist in any amount of time because you just leave at 11pm and you feel awful. Then you arrive at 5:45 in the morning, and I always had this doom when I finally got back to New York because all of this stress from whatever was happening in California was gone, and the second you touch the ground you’re like, “Okay now it’s all the things I sort of compartmentalized away - a friendship or relationship stuff.” The second you get back to New York it gets replaced.

“Landing” talks very specifically about drinking. In reference to the idea that sometimes I would have some drinks on the plane to try and fall asleep but then I couldn’t fall asleep so then I would show up in New York just...I don’t even know how to describe that state. And I’m laughing right now because it is ridiculous, but that also became my framing for coming back to New York. And getting back to New York just in time for rush hour and sitting in the back of an Uber for an hour and fifteen minutes or something as it all is just washing back over you and all you wanna do is get back into bed.

That is the very travel specific thing, but I think we are constantly burying emotional stuff in different places and trying to leave them there. Like coming home for the holidays or going to your parents home you have to put away all of your New York stuff and you’re like “ah, this is a feeling I haven’t had in a while.” That kinda stuff. So that’s a very big abstract amorphous thing, but trying to encapsulate it and talking about what it felt to take those flights. Again, the visual of every time you land you see Coney Island and then you land at JFK, trying to put these hyper-specific things into the song.

And to your observation, it is all about moving around, whether it’s driving around your town or flying back and forth. I did not make the connection in my own project when someone said, “Oh the first track is like you don’t wanna come back and the second track is that you’re landing,” and I was like “Yeah yeah, totally totally...”

Ayla: Love that that wasn’t on purpose.

Michael: Yeah, but I always like traveling. I don’t like traveling alone because I am a very people person. But without those two memories, I have no clue what this E.P. would have been about because I spent so much time bouncing around and then spending time at home, that it took up so much emotional space that it had to be the first thing to emerge after starting a new project cause that’s, I think, eternally on my mind.

Sarah: Yeah, like this revolving circle that keeps happening and keeps happening.

Michael: I think I wrote about it, but the last tid-bit in terms of the driving thing. I talk about rewriting those previous experiences and I’m afraid for it to come off as, like, “Now that I have a better sense of my identity, I’m thinking about those old memories in high school in a romantic way.” It’s not like I am imagining “What if we kissed in the Wendy’s drive-thru?” It’s not that. That’s not the memory. It’s “What if I had known what I was feeling?” And so I feel like that is something that is going to take longer to bring people into. I feel like I talk a lot about, “Okay, so now that I have a better sense of my queerness and my identity...” when I think back about those memories and those spaces and those car rides. Wouldn’t it have been nice to feel like a different way, or know what that thing that was going on actually was? Less so about when we were walking across the football field or walking across the cemetery, that it was gonna go in some direction that it was not going to go in.

Ayla: Yeah, that resonates so strongly for me. I really appreciate that message. I think a lot of people, queer or not, but I as a queer person super related to looking back on times where it’s just like, “Wow, how could I have been if I just knew how I actually saw myself as or who I wanted to be.”

Michael: And I absolutely did, at first, I was thinking, I was romanticizing. Because I was romanticizing them, I just didn’t really understand that that is what I was doing. But that to me, I don’t want that to be the message. I don’t want the message to be rewriting experiences I had with straight people and thinking that maybe we would kiss (laughs). That’s not the message.

Ayla: (laughs) I don’t think it’s coming off that way, so it’s okay.

Sarah: What do you feel like the message was for this specific album? Cause you talked a lot about collaboration, traveling, and queerness, but what was the exact message?

Michael: I think it is still being formulated, but as I talk more about it, and also why I am so grateful for both of you allowing me to talk more about it cause it’s helping me understand more of the things I don’t understand about this project yet. I know community is such a big word and it means a lot of things, but I feel like I am trying to understand my community in terms of my friends and relationships - past, present - and also my music community and people who are already working so hard to support each other and get through this insane moment and are trying to be an artist and any type of artist.

I do feel like there is a community thing here that’s like, you now know what the songs are about and those kinda things, but larger than that like the way they were built and created, I think is honestly just as weighted and what the message of this project is. I think it is self-aware, it’s like I know I’m an EP and a larger thing where there is a benefit to it and it’s detached from a monetary endeavor. So, for me, it just comes back to people and hopefully, whether it is people from my past with whom I am re-understanding our interactions or whether it’s people in my literal music community who I took for granted or did not have as a part of my explicit community.

I’m gonna work for you guys on trying to say that better, but it’s definitely coming down to those people. And it’s cool that some of those people, like Greg who I said before, I knew from high school, and he was an early music inspiration. He was absolutely involved and was around for those ridiculous nights where like 20 people would just go and run around our golf course at 1:00 in the morning and just be ridiculous, as I was trying to understand what anything meant about my interaction with half of the people there. I like how it’s twisted together in terms of processing your community as just like your friends and the music community.

“…now that I have a better sense of my queerness and my identity, when I think back about those memories and those spaces and those car rides...wouldn’t it have been nice to feel a different way...”

Ayla: Yeah, and this is kind of a big question -- it doesn’t have to be per say -- but I guess, how has your community experience shifted overtime? That could be a really long scale, but I know you’ve been in Hartford and now Brooklyn.

Michael: I think a couple things come to mind. In terms of music for example, and before I even was getting to experience some of these aspects of being a musician in Brooklyn, there were already smaller community oriented venues closing and stuff. Like I graduated in 2013 and immediately was playing music, and friends that I knew who had been playing music much more seriously or for a longer time were already telling me, “Oh this venue’s closing, that venue’s closing” and watching the Brooklyn music community see some establishments of their community disappear before I had even gotten to feel like I was a part of it.

It was a really interesting thing because that never stopped: venues kept closing. A lot of musicians I was first introduced to or got to see right after college had left New York cause there was less happening there for them. But then with COVID, you realize that the only thing that matters, it’s sensationalizing to say, but like venues are gonna close. They are gonna get bought by some massive company, we all know that stuff is gonna happen. And again this isn’t something I’ve been part of. I watched my friends play living room shows and backyard shows and watching them go on to do bigger and bigger things and without that community structure it would be totally different.

So my relationship with community is from the outside, I’ve been watching an existing community kind of morph and form. Working with Dylan and working with Funnybone - I don’t really know that I have a community in Hartford other than friends, but the opportunity to take a piece of music that is so ingrained in that geographical location and have both of you to talk to, and to have the label in general to collaborate with and reground, reconnect. Ya know, you’re the first person to insinuate I have any community in Hartford. That sounds so dramatic, but I haven’t really thought of this, but I spent 18 years of my life in Hartford and this was a huge opportunity to pay dues and get supported like that by that community. But it’s funny, once this COVID nightmare hopefully ends, it’s not like we’re going back to living the good life. We’re going back to the same struggle of building a community in cities that do not want you to have these spaces.

Sarah: During this crazy time how do you feel it’s influenced your art? Has it changed things?

Michael: On one hand, it’s the kind of thing that makes you not want to get out of bed, but on the other hand it’s when the stakes are... different. It’s one of the reasons I felt comfortable playing a bunch of guitars on the songs. Because I’m sitting in my apartment doing it plugged into my computer. Last time I made a record it was in a studio and it was so intimidating and big and it sounded so different. So, there’s a lot of negative stuff, but if I wanted to focus on the positive. It absolutely let me be like, “Fuck it, I’m sitting in my underwear with a guitar and just trying over and over again to make it happen.” And I think that happened because there wasn’t really another option (laughs).

And also, maybe help me get over the fear of sending an email or a text message to someone that I wanted them to be involved. Maybe I wouldn’t have done that if I felt like I had access to the people in my immediate vicinity. Maybe it would have felt scarier or more ridiculous to do that. But, in the end I think when it was all said and done, it was people in six different cities. I don’t know if that would have been the mentality if COVID hadn’t forced me to realize, “If I know someone in Berlin (I don’t know someone in Berlin) but if I did... why not? There’s no difference to working with someone you’ve always dreamed of working with 1,000 miles away.”

Sarah: That’s the cool thing about this project, you have been talking about all this collaboration and I feel like because of this time it was definitely fitting and a lot easier to reach out and have such a full amount of people on it.

Ayla: It’s just like maybe, I don’t know if I’m hearing you correctly, but it becomes the only way so that somehow loosens the pressure. Or like, I wanna work on these songs and I can’t put on a show so I guess all I can do is work on the song.

Michael: I think at a minimum it’s helped me get over the hump of some things I was afraid to do. Even like, going and recording a live version of the song, like I can play these instruments I know I can play these instruments. It's just there’s a lot of imposter syndrome and seeing these people who are much better at doing these things. I would sit and try to play these songs as if I was playing it to people. I would sit in my apartment and think, “What would it be like to play a little show?” Maybe that sounds ridiculous (laughs). There were no stuffed animals or anything involved.

Cover art for John Airfield's EP 1999, released by Funnybone Records

You can find John Airfield on Bandcamp, Spotify, and Instagram @johnairfield. Learn more about Morris Home through their website.