Exploring The Invisibility of Black Children Through Art

Nigerian-American visual artist Dr. Imo Nse Imeh is creating artwork that starts a conversation about two sides of a problem — the invisibility that Black children face and how society turns them into spectacles once they are no longer invisible.

Written by Jasmine Jones

Photographed by David Sierra

On the evening of February 26, 2012, a 17-year-old unarmed Black teenager was followed, confronted, shot, and killed by the neighborhood watchman in Sanford, Florida. What followed shortly after was the turning of that 17-year-old, Trayvon Martin, from a human being to a concept; from a teenage boy to a public spectacle. Seven years later, as we continue to speak about Trayvon Martin (and the multitude of victims from similar cases) as concepts rather than human beings, there is a need to have this conversation about what we’re doing when we speak about these victims. Nigerian-American visual artist Dr. Imo Nse Imeh has started this conversation with his artwork, which discusses both sides of the problem, from the invisibility that Black children face to the moment when society turns them into spectacles for the public to tear apart.

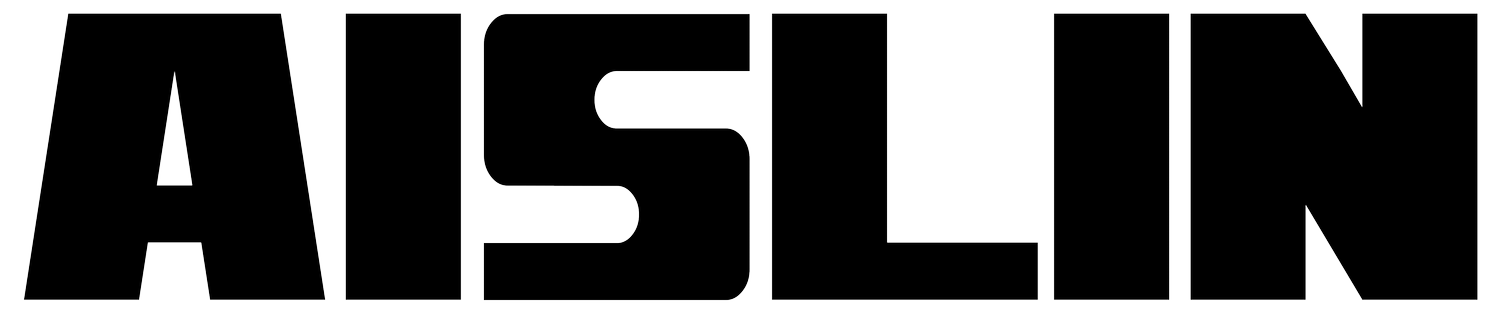

We met at his studio on a Sunday afternoon, which had been turned into an exhibition space for his latest project, titled 17 Years Boy: Epilogue. “I’m trying to get used to the idea of people just all up in the space, because this is the studio, this is my studio,” he says, as a few guests casually walk through the space, browsing the work he has on display. As we begin discussing his artwork and the inspiration for 17 Years Boy: Epilogue, he explains that many of his projects have dealt with Black children and invisibility. “I think that invisibility is one of the most dangerous things that a group of people can face, because when you’re invisible, anything can happen to you,” he states, using prisoners as an example. “Society has found a way to decide not to think about them, and so they’re extremely susceptible. They’re vulnerable in a way that the rest of us aren’t because we’re visible, they’re not.”

More recently, the Lifetime docu-series Surviving R. Kelly shows the inherent Black invisibility when it comes to children. “Black girls are invisible,” Dr. Imeh simply states, “And so, they can become preyed upon, even by music stars - if you believe that he did this.” Dr. Imeh finds his inspiration through a range of things, from early 1900s children’s books that depict Black children in ways that are less than human, to the mass abduction of 276 Chibok girls in Nigeria by the terrorist group Boko Haram. “I started addressing these different things in my artwork,” he says, “I had never created children before, but my work has had, I guess you would call it, a social justice lens. And so that is how I started working on 17 Years Boy.”

“I think that invisibility is one of the most dangerous things that a group of people can face, because when you’re invisible, anything can happen to you.”

As an Associate Professor of Art and Art History at the Massachusetts Westfield State University, Dr. Imeh started 17 Years Boy last year, after an unsettling rash of racially charged incidents took place on the university’s campus. Based off of his earlier series titled Ten Little Nigger Girls, he started a second series titled Ten Little Nigger Boys. Through his website, Dr. Imeh explains of the first series:

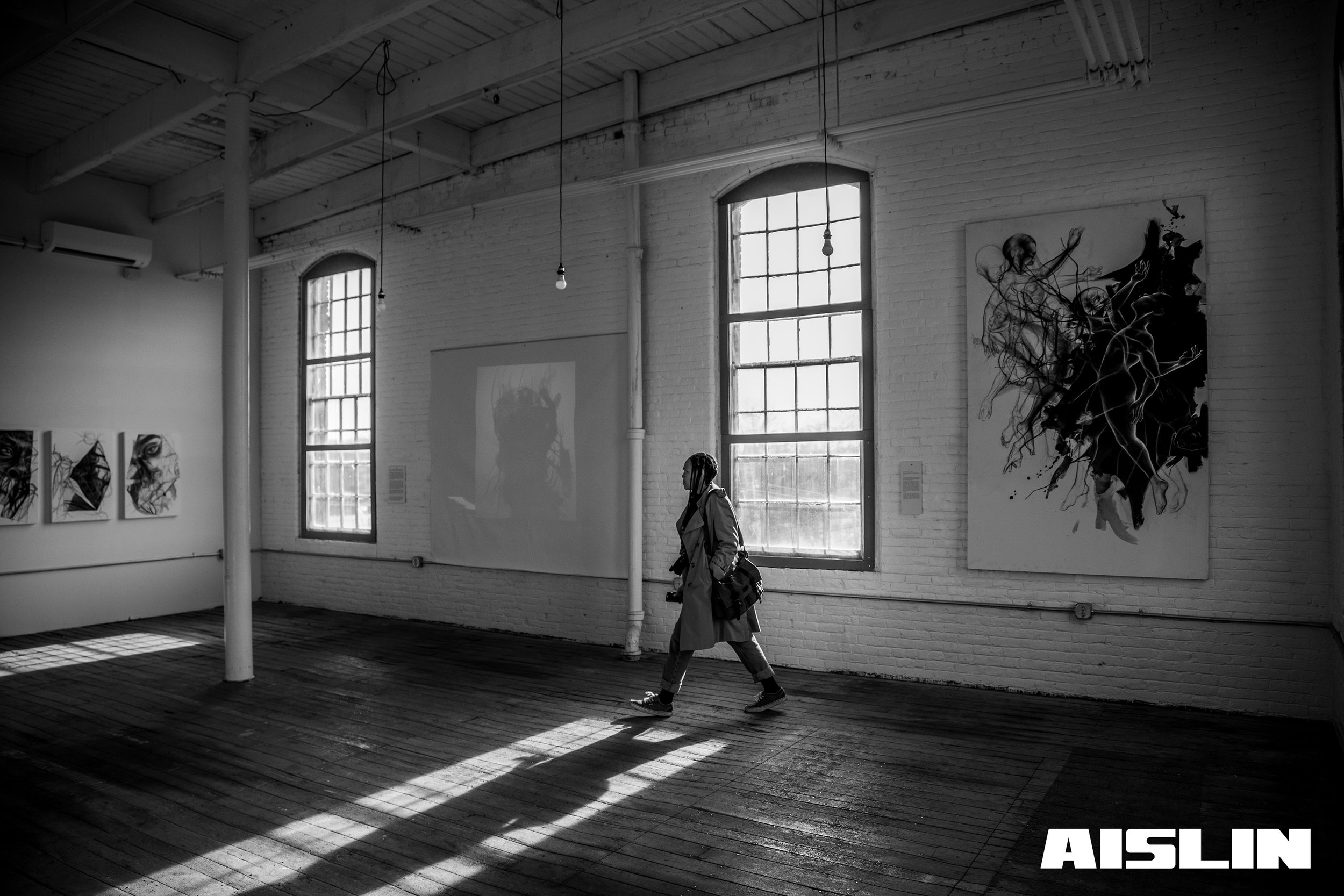

Ten Little Nigger Girls is a series of ten large-scale drawings that addresses the present-day reality of Black girls in different states of danger within the American and global cultural contexts. The project is a retelling of the 1907 children’s book and nursery rhyme, Ten Little Nigger Girls, by Nora Case, which features a cast of ten Black girls, who are each eliminated from the story one-by-one, sometimes in horrific ways (for example, one is burned alive, another is eaten by a bear).

My art features contemporary Black girls in various states of danger, in the present-day, in the spirit of education and conversation, to examine the language, history, and realities of race in America, and the unsettling ways in which Black children specifically have been imagined in the American social economy over the past century.

My project focuses on the imagination of Black children–both historical and present-day concepts–in spaces of danger, primarily because of the vacuum in scholarship about the body of the Black child in visual art and literature studies. These drawings open up an important door for such a conversation to take place.

When he began working on the series which focuses on the boys, he initially wanted to create ten drawings featuring ten contemporary boys whose situation or story is emblematic of the dangerous invisibility that Black children face. “I started on the Trayvon Martin piece in my studio, but I couldn’t figure out how to get going with it. When this rash of racist incidents happened on Westfield State’s campus, something just clicked and before I knew it I was hauling a 6 foot canvas and all of my supplies in a van to Westfield,” he explains.

He wasn’t sure where exactly the painting would be completed, but he knew it was something that had to be done on his campus, as a way of addressing the things that were happening at the time. Dr. Imeh describes the incidents, saying, “People were writing racist things on the dorm doors of Black, female students, such as ‘niggers live here’ or ‘go home niggers.’ You could imagine how unsettling it would be to feel unwelcome in your home away from home. I wanted to deal with this from the lens of a historian and also from the lens of an artist, so this was the perfect opportunity.”

Forgotten Girl from the Ten Little Nigger Girls series. Charcoal, pencil, india ink on canvas. 48 x 60 inches, 2015

"There’s one level where you’re invisible, the other thing that you don’t want to be is a spectacle, and I was a spectacle at that moment.”

In a performance space on campus, he completed a large scale portrait of Trayvon Martin over a 17 hour period, with each hour marking one year of the teenager’s life. Dr. Imeh painted at scheduled times each day, allowing an audience to come and watch while he worked, as he was interested in the idea of the Black spectacle in the performance space.

“So here I am on a PWI, a predominately white institution, this youngish, Black professor, dealing with this young man who was a public spectacle, surrounded by a portrait gallery of young men who themselves had become spectacle-ized: some of whom who had been the spectacle during lynchings in the early 1900s,” he says of his performance, “It was this whole idea of using the performance space as a great big symbol of the Black male spectacle and the dangers that come with that. There’s one level where you’re invisible, the other thing that you don’t want to be is a spectacle, and I was a spectacle at that moment.”

Using the 17 hours to tell the story of Trayvon Martin growing up, Dr. Imeh started with staining the canvas red and black to symbolize him unborn, and ended with cutting up the canvas, symbolizing the life that was developing and growing abruptly being cut short. He was sure to be the person to make the first cut, because he himself felt just as complicit as George Zimmerman should feel. “I used his name, I hashtagged without knowing the full story, I used him as a concept. Even if I was trying to do the right things, I was using him in a way that dehumanizes him still,” he states. “There’s no way to have a conversation about him now because he’s such a public entity. There’s no way to talk about him as just a human, as a boy. And so, the project was trying to do that, make him a boy, but in the process of doing that it re-emphasized the fact that we can never see him as only a boy anymore, he’s a symbol. And that bothers me.”

Now, one year later, using pieces of the originally destroyed painting, Dr. Imeh created 17 new works of art symbolizing, in his own words, “the challenging, yet beautiful, journey down the path of healing, to transform the horror of unspeakable tragedy into a renewed sense of life and celebration.” Dr. Imeh clarifies that even though some people didn’t understand why, the painting was always meant to be cut apart, explaining, “If it wasn’t destroyed then this project would have been meaningless. That piece was a proxy for Trayvon Martin. He’s not alive right now, so that piece had to be destroyed.”

Seraph. Oil paint on canvas. 2018

Wisdom Becoming (detail). Oil paint and acrylic ink on canvas. 2019

Although he notes that his current projects all embrace a strong element of social justice, he knows that that isn’t his ultimate goal with the artwork that he creates. “My situation is not the reason why I make art,” he says. “I’ve always made art. If everything was right with the world, I would be making art regardless.” He believes that we’re all given one lifetime, and if we’re lucky, it’s filled with at least 80 years of full mobility and the ability to share our unique voices and set of visions, some of which he believes will never be realized.

“I don’t believe that all of the visions we’re given are for us to realize because if I could realize all of my visions, the things I want to see, I would probably be 400 by the time I died,” he elaborates, “My goal is not to be one thing, but to do precisely what God has animated me to do with my art, and at this point in time, it is this conversation about Black invisibility in children. I would love it if there was ever a time when that didn’t have to be the conversation, but I’m just going to keep making things until I can’t anymore. That’s my goal.”

When thinking about his upcoming projects and the long term impact his artwork will have on its viewers, Dr. Imeh hopes to create cool art that makes people experience the world in a different way. “If my work can catapult people into a different thinking space,” he says, “Even for a moment, and then allow us to have a conversation, I’ll be really happy about that." He felt a moment of that during 17 Years Boy, as they began to destroy the canvas in the 17th and final hour of the performance.

“The thing that happened in that room when we were cutting up that canvas, you would have to have been there,” he recalls. “There was nothing that could capture the energy of that space. People sent me emails like, ‘What the f was that?’ Those were the emails. And I’m like, I don’t know, but what was cool about that was that none of us knew. None of us could own that as ours. The art took us into another place, and that can’t happen all the time, but if I could be a part of that more often, that’s what I want, that’s cool.”

A Conversation with Crows (detail). India ink, acrylic paint, and charcoal on canvas. 2016

Dr. Imeh poses in front of Study of Two Angels in Conversation

Dr. Imo Nse Imeh is a Nigerian-American visual artist and scholar of African Diaspora visual culture and aesthetics. He is an alumnus of the Yale University Graduate School, and presently an Associate Professor of Art and Art History at Westfield State University in Massachusetts. You can learn more about Dr. Imeh and his work through his website at imoimeh.com, and follow him on Instagram @imoimeh.

His exhibition 17 Years Boy: Epilogue is running from February 8th - March 15th, 2019 at Readywipe Gallery in Holyoke, MA.